Charles Wesley’s Night In The Condemned Cell

Share

In 1735, the newly ordained Anglican clergyman, Charles Wesley, had accompanied his brother, John, on an ill-fated missionary trip to the new American colony of Georgia.

The settlers – many of whom had gone there to escape the rigours of conventional religion – found the Wesley’s high-handedness and strict application of the ‘letter of the law’ too much for them and reacted with open hostility towards the brothers.

What added to the strain the Wesleys were feeling was that neither of them had any assurance of their own personal salvation. In fact, their very missionary activity in Georgia was intended to ‘save their souls’ by good works.

Perhaps inevitably, Charles’ sensitive and poetic nature collapsed under the strain and after only a year in Georgia he was invalided back to England to be followed some time later by his dejected brother.

However, on arrival back in England Charles found his friend George Whitefield had discovered the new birth and was preaching to huge congregations. Another influence was a Moravian pastor, Peter Bohler, who began to teach in religious societies attended by the Wesley brothers on the true nature of faith.

In 1738, Charles moved in with a ‘poor, ignorant mechanic’ named William Bray, because he saw that, in spite of Bray’s lack of education, the man had a real and living relationship with the Saviour. Much of this time, Charles was confined to bed because of ill health, yet he earnestly sought God for the peace he saw in his friends.

In May, Charles and his group began studying Luther’s ‘Commentary on the Galatians’ together. As Charles was reading this in a society meeting, one of the members, William Holland, was dramatically converted and a few days later Charles himself found peace through the words of Paul, “the Son of God who loved me and gave himself for me.” Charles called this his ‘Day of Deliverance’ – it was Whit Sunday, 21 May 1738.

And Can It Be?

Two days later, Charles composed a hymn ‘upon my conversion’. This hymn turned out to be one of the greatest gospel hymns ever written, a hymn that even today burns with the joyful conviction of a man who has found the greatest of all treasures after a long and heartbreaking quest:

Charles’ conversion had a dramatic effect. In the first place, he was able to rise from his sick bed a new man. Secondly, his heart was filled with an evangelistic zeal to share his new-found faith with everyone he could find. He even went so far as to have himself locked in a cell with a group of condemned criminals, all of whom he led to Christ before their execution.

On 18 July 1738, two months after his conversion, Charles Wesley and his friend, Bray, had spent the week witnessing to inmates at the Newgate prison. One of the men they spoke to was, in Wesley’s words, “a black slave that had robbed his master.” He was sick with a fever and was condemned to hang.

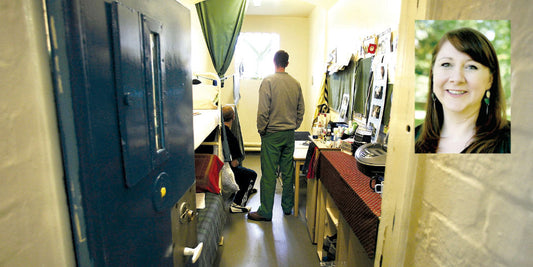

Wesley and Bray asked if they could be locked in overnight with the prisoners who were to be executed the next day. This was an incredibly brave (some would say foolhardy) thing to do as the situation could well have turned out extremely dangerous for them. After all, the men concerned were all condemned and would have lost nothing by harming or even killing the visitors. It was sheer love of souls that made Wesley and Bray stay with them in the stinking prison cell.

That night, however, Wesley and Bray spoke the gospel. They told the men that “one came down from heaven to save lost sinners.” They described the sufferings of the Son of God, his sorrows, agony, and death.

The next day when the condemned men were loaded onto a cart and taken to Tyburn to be hanged, Charles went with them. Ropes were fastened around their necks so that the cart could be driven off, leaving the helpless victims swinging in the air to choke to death.

The fruit of Wesley’s and Bray’s night-long labour was astonishing, as Wesley wrote:

“They were all cheerful; full of comfort, peace, and triumph; assuredly persuaded Christ had died for them, and waited to receive them into paradise. The black... saluted me with his looks. As often as his eyes met mine, he smiled with the most composed, delightful countenance I ever saw.

“We left them going to meet their Lord, ready for the bridegroom. When the cart drove off, not one stirred, or struggled for life, but meekly gave up their spirits. Exactly at twelve they were turned off. I spoke a few suitable words to the crowd; and returned, full of peace and confidence in our friends’ happiness. That hour under the gallows was the most blessed hour of my life.”

This article was taken from issue #42 of Heroes of the Faith.