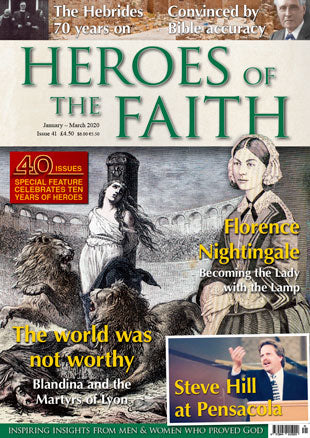

Blandina and the Martyrs of Lyon

"The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church"

It was 177AD in the City of Lyon, and the churches were under severe threat from persecution stirred up by the mob and executed by the Roman authorities. Having been conquered by the Romans, Lyon had become a proudly cosmopolitan city, teeming with officers, administrators and merchants drawn from across the Roman world. And as the effective capital of Gaul since the time of Augustus, it possessed a temple complex dedicated to the former Roman emperor who, of course, was now regarded as a god to be worshipped along with many others. Altars to other gods abounded, including one to Cybele, a primal nature goddess worshipped with orgiastic rites by castrated priests.

This made the situation of Christians in the city precarious. Although the formal, state-sponsored persecution unleashed by the likes of Nero had petered out, the fact that Christians – like the Jews – did not worship the gods or celebrate their feast days, made them suspect to the populace in general. And whereas the Jewish religion enjoyed protection under Roman law, Christianity – this strange offshoot of Judaism – enjoyed no such amnesty from persecution.

The very distinctiveness of how Christians worshipped made them objects of much scandalous gossip among the population in general. After all, they had no image of a god to worship, so this made people suspect them of being ‘atheists’. What’s more, it was rumoured, they committed incest, worshipped the genitals of their elders and bishops, and even indulged in cannibalism. While Christians indignantly refuted these claims, fake news – then as now – tended to carry its own stigma. There was no smoke, surely, without fire, reasoned the heathen populace, their hostility stoked by the fact that many of the Christians were immigrants who had settled in the city from Asia Minor.

... story continues