Global Impact of the Cross and the Switchblade

Share

If the story behind God’s work in David Wilkerson’s ministry was unlikely, so was the story behind its telling in the multi-million-copy best-selling book, ‘The Cross and the Switchblade’.

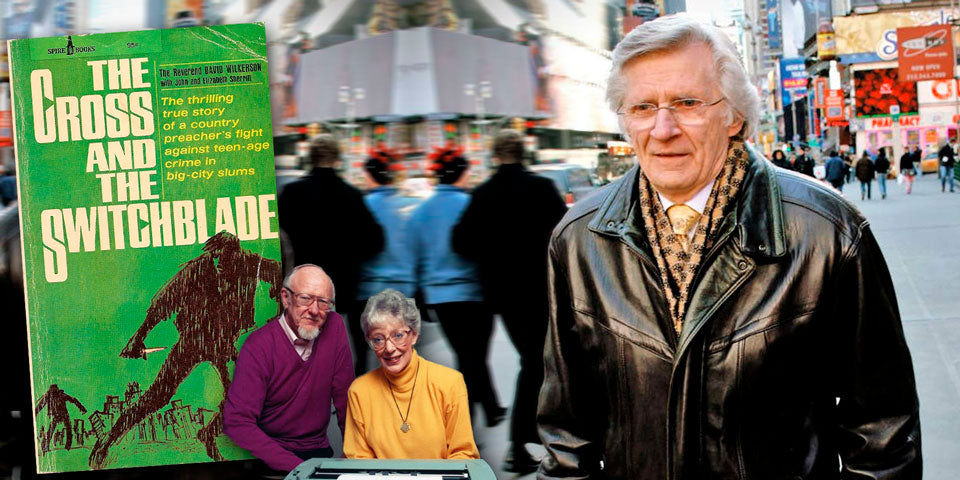

For a start, the couple who acted as the ghost writers, John and Elizabeth Sherrill, were not David’s type at all. Living in the wealthy suburbs of New York City, the world which they inhabited was intellectual and ultra-rational, and until recently they hadn’t had an active Christian faith themselves, despite being writers for ‘Guideposts’, an inspirational magazine founded by Norman Vincent Peale.

The Sherrill’s initial contact with Wilkerson came as a result of a project they had embarked on to investigate the so-called ‘charismatic renewal’ and the phenomenon of speaking in other tongues that was sweeping the church in the 1960s. When the Sherrills heard about what David Wilkerson was doing and the fact that he spoke in tongues they decided to go and meet him.

What they found as they investigated David’s story and the work of the fledgling Teen Challenge, was that it was not just about speaking in tongues, but that at the centre of it was the power of God’s Spirit to transform damaged, broken and helpless lives – sometimes in an instant.

“It was a window opener on to another world,” said Elizabeth. “It was a world very different from our own, and one we knew nothing about.”

What they also found was a young minister, driving himself to exhaustion, sacrificing family time in a pioneering work, and nursing ulcers he had developed from the stress of it all.

They also heard some pretty amazing stories about what happened on the dangerous streets where Wilkerson ministered, like the time David told them he and a trumpeter went out for an evangelistic meeting and over 300 people gathered on a street corner to hear him. If the Sherrills were initially sceptical of this tale, all doubts vanished when they checked it out with the local police and found out there had in fact been more than 500 people gathered at the meeting!

Cold turkey

Although the Sherrills were no strangers to the darker side of human nature, they were shocked when they visited the Bedford-Stuyvesant headquarters and heard the screams of young addicts suffering ‘cold turkey’, along with the horrific stories of group sex and bestiality among those who were scarcely older than children.

But equally eye-opening were the miraculous deliverances those young addicts experienced, and the Sherrill’s first-hand view of Wilkerson’s own demeanour: “His eyes, his personality, his commitment, his intense love for the people he was talking to – the word that keeps coming to mind is fearless,” Elizabeth recalled. “He confronted gang members and other unsavoury types with great courage. He just read them the riot act, telling them that God loved them, and that he would love them.”

Even more challenging for the rationally-minded Sherrills (and later the sceptics at the Guidepost offices) was the sheer number of miracles that David claimed had taken place – supernatural stories of conversions, deliverances and transformed lives. When on investigation they found every account to be verifiable they concluded that the heart of the story was, “the power of the Holy Spirit to move into the world right now and change things.” Quite different from the virtually deistic view of many denominational churches of the period!

Even after all the verifications, the Sherrills had the problem of which miracles to include in their reports – there were so many of them – and also to convince the sceptics at the Guidepost offices that the stories weren’t fake. In the end the editor, Len LeSourd, agreed to run the story in three parts – a first as the magazine had never run a multipart story before. The response from readers was so overwhelming that it was quite obvious a book had to emerge.

But how? For that to happen it would need a publisher and a financial advance of some $5,000 to meet the Sherrill’s expenses in the three years they would take in writing the book. Wilkerson in fact had put out a ‘fleece’1 asking God that if he wanted the book published both needs would be met.

The answer came from a most unusual source – a Jewish secular publisher named Bernard Geis, more used to bringing worldly sensational bestsellers2 to the market than those of spiritual transformation. However, when he listened to John Sherrill’s pitch about the proposed book, with its stories of gang members, switchblades and heroin addiction, it was the sensational side that appealed to Geis and he agreed to fund a $5,000 advance.

The rest is history. Published in 1963 with a lurid green cover and racy image of a knife-wielding gang member, ‘The Cross and the Switchblade’ flew off the bookshelves to a world hungry for the reality of the power of God. In all, around 16 million copies have been sold in over 30 different languages, with many school children reading the book as set texts in religious education classes. Written in the Sherrills’ inimitable, easy, journalistic style, many people have begun reading it and then stayed up all night as they found they couldn’t put the book down!

One potential problem lay in the (then) controversial element of speaking with other tongues which was originally written into the last chapter. Both Wilkerson and the Sherrills were concerned about whether it would hurt the book’s sales and even harm the financial side of the ministry of Teen Challenge. However, when they put the matter to Bernard Geis, the cigar-chomping Jewish publisher told them he wanted more on the subject! Phenomena like speaking in tongues made for sensational journalism, so why were they afraid of it? So in the rewrite the last chapter became two!

Speaking in tongues

Looking back, Wilkerson was able to see the hand of God in directing them to a secular publisher. In those days miracles such as seen in Teen Challenge – let alone speaking in tongues – would have been considered far too ‘hot’ for any Christian publisher to handle. However, once the book was out it became a tremendous instrument for the spread of the Pentecostal and fledgling charismatic movement, as people saw the reality of the Holy Spirit at work.

Interestingly the only place where the book did not sell well was in Scandinavia, where it was found the publisher had deleted the last two chapters as being thought too controversial. However, once Wilkerson insisted the chapters were put back in, sales took off, quickly matching those in other countries.

The book also turned out to be a prophetic warning: the drug scene was very soon not confined to the inner-city gangs but spread to middle-class areas. Though the later outreach to those more affluent addicts might not have been so sensational it was nonetheless much needed and The Cross and the Switchblade prepared the way.

Interestingly the book never made anyone rich as Wilkerson’s royalties were ploughed back into the ministry. Then unexpectedly the publisher went bankrupt, something that stalled The Cross and the Switchblade’s income for years, before the case was settled and the rights reverted to Wilkerson and the Sherrills. But for the three authors it never was about making money but about offering a wondrous story of a living Christ to a church at that time lacking in power and a world starved of hope.